Understanding African Wild Dog Movement

In January of 2018 I spent two weeks in South Africa’s uMkhuze Game Reserve as a volunteer with the conservation group WildlifeACT. Many animals in the reserve are equipped with tracking or radio collars and every morning and evening we would use VHF radio telemetry to track wildlife throughout the park, paying special attention to the lions, cheetahs, and wild dogs so as to monitor their health and welfare. In the afternoons we would record camera trap data and compile notes from our previous work to create a database of animal movements and notes.

After my time with the project, I received tracking collar data from individual wild dogs in Somkhanda Game Reserve and used programming language R to examine the movement patterns and known locations of the dogs. Studying the data revealed the distance covered between observations, the turn angle between consecutive points, the elevation of the dog at each observation, and if the animal was using a road as a corridor for travel.

This project is still very much a work in progress, however the ultimate goal is to create a context-sensitive correlated random walk model that simulates the movement of the dogs. Using the known observations and patterns as parameters, the hope is to create a simulated agent that “chooses” a path on a raster based cell-by-cell approach where each cell contains environmental characteristics. If I can get an agent that is influenced by these factors to move in the same way as the recorded movement of the dogs, conclusions about the ways in which the dogs select their path of travel can be made. Understanding how environmental factors correlate to the observed movement patterns of wild dogs strengthens knowledge of their behavior and has a broad range of implications for management strategies.

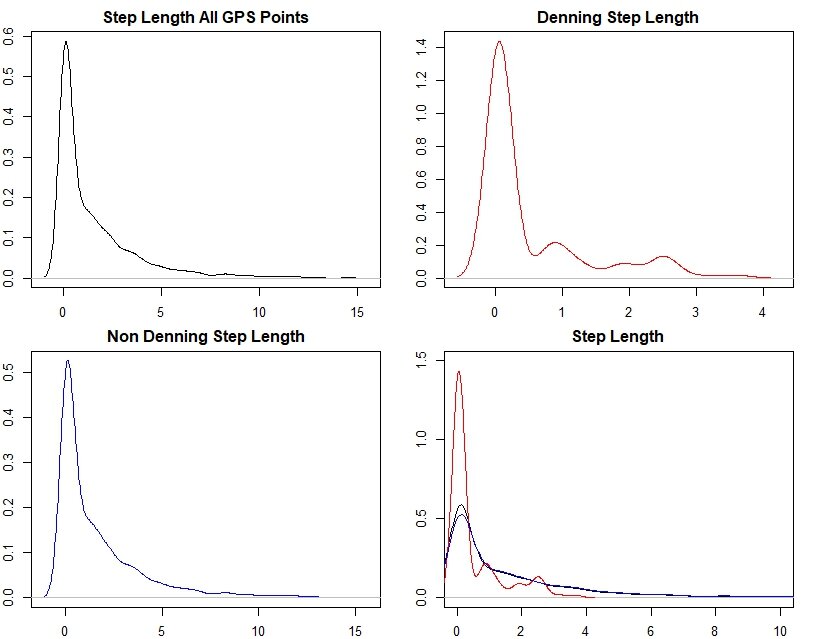

Denning and non-denning seasons are best seen in the variations between distances traveled between points. During the denning period the dog remained nearly stationary the majority of the time, while during the rest of the year the same dog moved up to 13 km between observations.

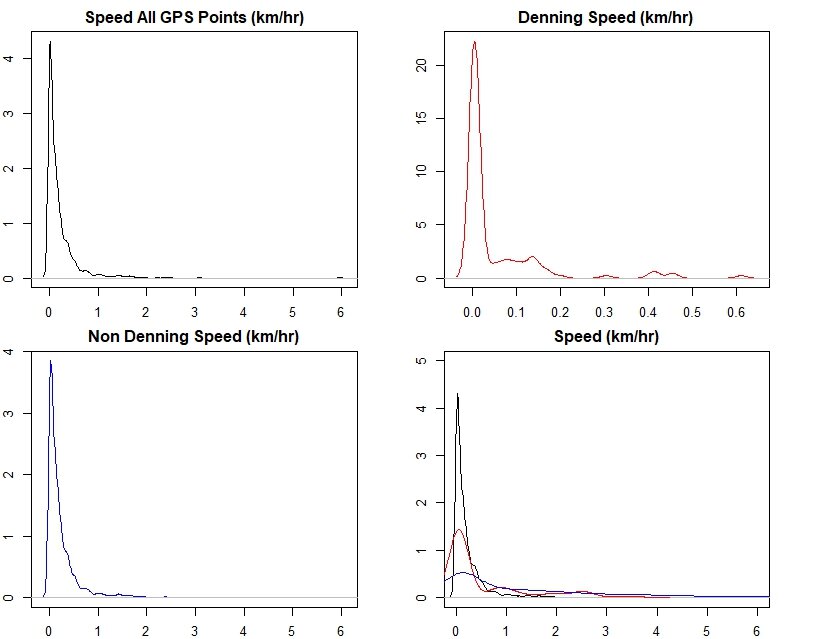

Not all observations were taken over a uniform period of time, so speed is a good way of normalizing the data. The same patterns of denning and non-denning movement are seen.

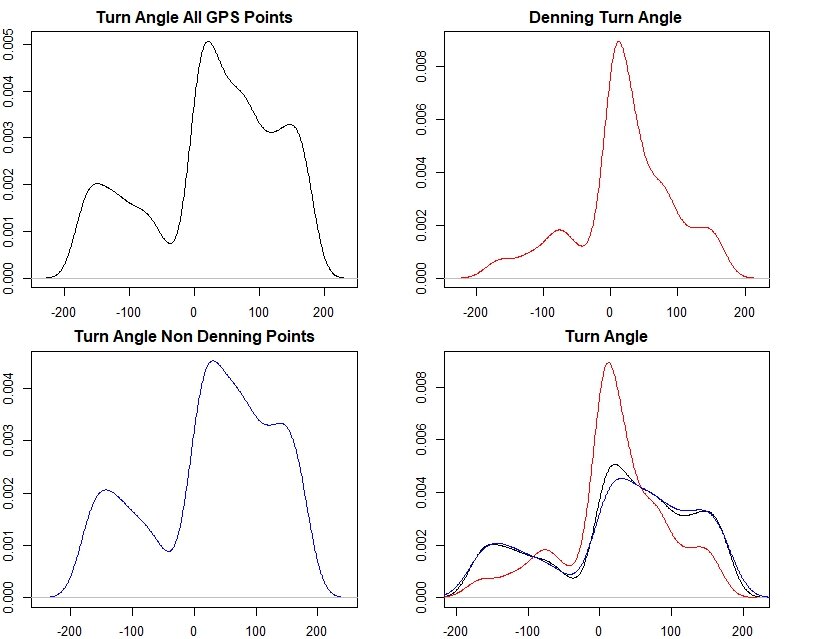

The turn angle between consecutive points, ranging between -180 (counterclockwise turn) and +180 (clockwise). While a turn angle of zero usually indicates purposeful forward movement, the turn angle during the denning period may be attributed to a general lack of movement.

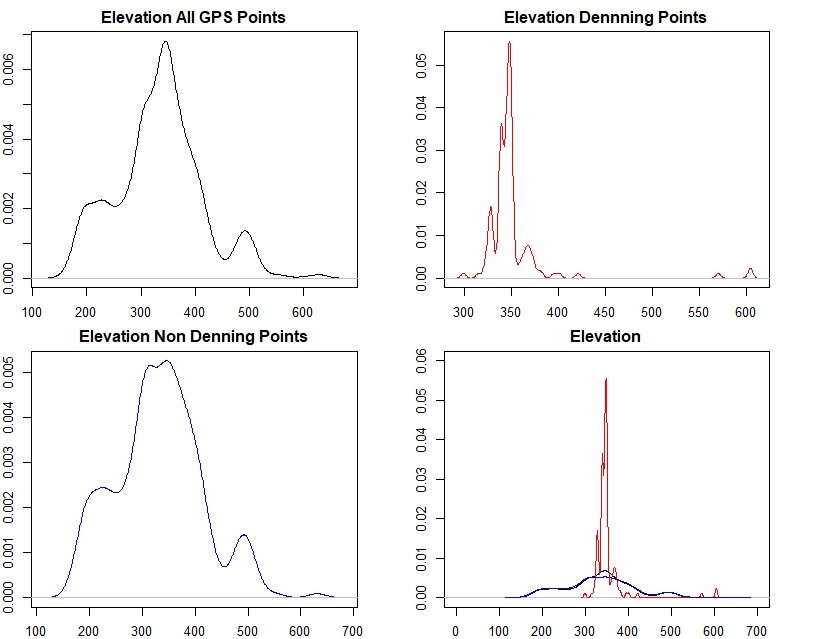

A distinct difference in elevation is seen during denning versus non-denning periods, however the question that must be answered is whether the dogs deliberately chose a denning location based on elevation, or if other factors were at play and the spike at ~350m elevation is simply due to a prolonged time spent in the same spot.

The conceptual workflow of my proposed context sensitive correlated random walk model